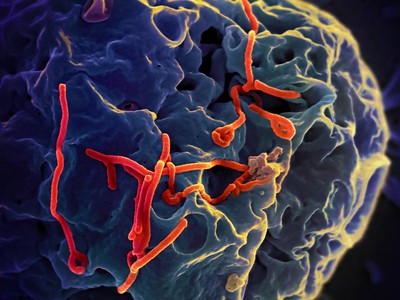

The world watches Wuhan with a growing fear. In an unprecedented move, the Chinese government has quarantined entire cities and tens of millions of people sit inside their homes fearful of what is occurring outside. The 11 million inhabitants of Wuhan are seen as the genesis point of the highly contagious version of the new coronavirus that is rapidly gathering speed.

Videos on social media are showing a medical system at breaking point, with doctors suffering from overcrowding and never-ending shifts; people collapsing on the streets; and hospitals corridors filled to capacity with people (some potentially deceased) who, if they aren’t infected, will probably be soon.

Global pandemics are a terrifying scenario. By the time the ‘big one’ hits, it will likely be too late to contain it. International travel patterns are now so widespread that many countries will find themselves with live cases before the first ones are properly diagnosed. To the average person, the decision to stop going to work in order to avoid the chance of infection becomes an incredibly difficult one to make. As with many devastating events, the wealthy are more likely to have the means (or flexibility) to protect themselves while so many others exist on fear and a prayer.

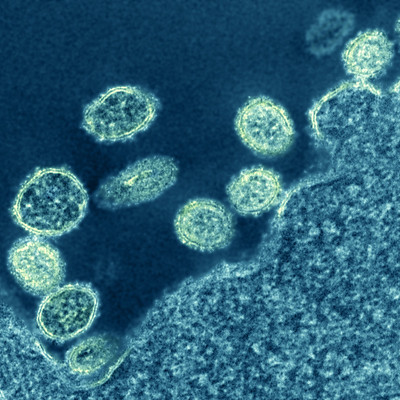

The nature of the new coronavirus is highly disturbing and there are serious questions around the extent to which the Chinese government has tried to suppress news of its infectious spread. But it’s the nearby location of the Wuhan National Biosafety Laboratory, China’s only biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) lab, that has people wondering whether the research done on lethal pathogens in this lab might have something to do with the recent outbreak. Completed just two years ago, there were numerous concerns raised about the nature of the lab and China’s development of high-level pathogen facilities that, even if they weren’t used specifically to develop bio-weapons, could lead to the unwanted release of highly dangerous and contagious viruses.

We might never know whether the current coronavirus outbreak emerged from this BSL-4 lab (located within miles of the city centre), but there are precedents that raise serious questions about these highest-level containment labs and the nature of research done in them. With more than 50 BSL-4 labs around the world (United States being the most prevalent with 13) renewed debate needs to be raised about their purpose, regulation and necessity.

In 2007 an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock in the UK was traced back to a research laboratory; although readily contained, it showed that even modern standards are not fail-proof. The UK government is keenly aware of such dangers, following the outbreak of smallpox in 1978 that led to the deaths of dozens of people and originated in pox virus laboratories at the University of Birmingham.

These mistakes aren’t just a thing of the past. In 2014 the FDA investigated the deeply concerning discovering of six vials of the virus that causes smallpox, along with hundreds of other pathogens, that had just been left aside in an unmarked cardboard box.

Indeed, the reason that people are so concerned about the proximity of the Wuhan BSL-4 lab to the outbreak is because we have already seen such tragic accidents take place before. There have been at least six accidental releases of the SARS virus since it spread in 2003, four of them from a lab in Beijing. It is also widely accepted that the H1N1 virus (swine flu) was essentially dead and gone before research labs began to produce it again, potentially leading to the deadly global outbreak of 2009.

Even more concerning are projects that don’t just seek to study and understand certain deadly viruses, but are actually attempting to make them more deadly. It seems that this kind of research in particular should be heavily curbed and even banned entirely, except perhaps for in the most isolated environments (Antarctica sounds good!). There should be limits placed on viral research, just as we do with genetic research and as are placed on every other element of human society.

From just this small, but worrying list of examples it is clear that there is an undeniable and consistent risk to human society from this research around the globe. It’s therefore important that a broader conversation takes place and the benefit/risk of these projects needs to be publicly debated and given more scrutiny under international law.

There are, of course, some obvious benefits to conducting this kind of research. It helps us understand pathogens and how to respond to them; advances the medical sciences in a wide range of areas; and breaks open new fields in treatment and prevention. We certainly need to understand how to deal with a pandemic when they occur. Perhaps it’s even necessary to defend ourselves from biological weapons that might be developed in the future.

It is this last area that creates the context of ever-present danger, making it unlikely that this research will be curbed to any real degree. Governments around the world are conducting viral research with highly deadly pathogens, which means that they might be used against innocent civilians and that provides the defense justification for others to continue their own research. Unfortunately, the most likely outcome of this is that the victims are the government’s own citizens through human error or unforeseen flaws in containment protocols.

Direct use of this research in an active attack is in clear violation of the Biological Weapons Convention, however the research itself still needs to be recognised as dangerous and potentially beyond the boundaries of acceptable risk. Indeed, one of the key suspects in the anthrax-mailing terror attacks of 2001 in the United States was a researcher at the CDC lab at Fort Detrick. Even though this suspicion has been contested, it shows that the best containment protocols can’t halt the actions of someone wanting to actively cause harm once they have access to deadly pathogens.

The outbreaks that have emerged from viral research labs so far have been relatively low impact, particularly on the scale of global pandemics, but this does not undermine the seriousness of the issue. If the recent outbreak in Wuhan can be linked to the newly created research lab there – which we all must admit is a real possibility – then we need to reassess the purpose of such labs and their legality on a global scale.

Thankfully, we have seen some recent moves in the right direction. The long-running biowarfare research conducted by the CDC at Fort Detrick has recently been halted following more extensive safety and risk audits – hopefully a sign of further drawback in these areas around the world

This kind of research pushes scientific endeavour while allowing for cutting-edge medical research, but it also leads us into areas that can threaten human existence on a similar scale to weapons of mass destruction. The benefits might be substantial, but the risks are also extremely high and often these programmes are conducted without the consent (or even knowledge) of civilians who live nearby.

Safety standards in BSL-4 labs are, by definition, already extremely high. However, in order to maintain public safety, such research should be conducted in remote geographic areas; should be public and transparently tracked; protocols of ‘exit quarantine’ should be in place; stricter auditing should occur; and research that aims to make viruses more deadly or virulent should be banned entirely.

Human society has long held cautionary tales of our own hubris and misguided tendency to feel that everything should be under our control. When it comes to research conducted into unpredictable and difficult to contain pathogens, we need a new public debate about the boundaries of our endeavours and where the lines should be drawn.

This isn’t just a luddite aversion to scientific advancement, but rather a call to acknowledge that there are some areas of research that have potentially dire consequences that can’t just be brushed away. Because the advancements made in these research labs are not always going to be worth the risk to the lives and wellbeing of millions of people around the world.

Header Image by Thierry Ehrmann, Creative Commons