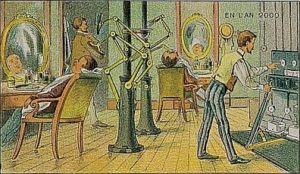

Image above by Ken Clare (CC, Flickr)

Automation is a topic that has long been of interest to futurists. I first put a marker down in 2010 with two prediction posts and it has proven to be an area of increasing relevance surrounded by a growing call for attention. It will be interesting to see whether this develops into a long-term policy response or falls to the wayside as another flavour of the month dropped for something new. Indeed, the impact and uncertainty of the UK referendum could easily contribute to that…

Putting that aside, there has been a noticeable increase in activity around the topic in recent months. The Financial Times named Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future their book of the year for 2015; the Economist ran a conference last week on Navigating the Changing World of Work; the Oxford Martin School continues to publish their groundbreaking research; and Chatham House is today hosting a high-level conference on the Future of Work which dedicates significant time to questions arising from automation.

Even amongst all of this it’s a tricky subject to get our heads around, primarily because it is one of those areas of technological advancement that will emerge very quickly. It won’t necessarily look like it’s going to happen on a large scale – until it suddenly does. At the moment, not many people outside of the tech sector are really taking the notion very seriously. Policymakers aren’t yet ready to prioritise the issue, it seems, despite some very clear indicators from the private sector that shifting business models are already bringing some deep-seated repercussions.

The impact of automation came back into the forefront of my attention upon reading Paul Mason’s book PostCapitalism: Envisaging a Shared Future which was released at the end of last year. His passionate take on the subject, and the idea that capitalism s being systematically undermined by the fruits of its own innovation, was a powerful rallying call that he has continued to make convincingly (read my full review of the book here). More recently, I have been at three different events that explored the subject – either tangentially or directly – and it was fascinating to see the different ways the topic is being treated.

The first of these was a conference at Goldsmith’s College run by the Political Economy Research Centre (PERC) – Beyond the Zombie Economy: Building a Common Agenda for Change – that aimed to explore viable economic alternatives to the predominately neoliberal status quo. Whilst covering everything from systems-based modelling, to the impact of debt, to feminist economics, the first day of the conference had no mention of the shift that automation might bring. I was not alone in thinking this was an omission, and whilst I was looking for a good moment to raise the question it popped up from others in a number of different sessions on the second day. The response on both occasions took on a quite dismissive tone. Automation (or mechanisation, as it was referred to, more on that in a moment…) was seen as a fanciful and unrealistic framework to place discussions about the potential for new economic systems.

I found this response intriguing, particularly given the topic of the conference and radical makeup of its audience. The closest it got to a serious discussion on the issue revolved more around Universal Basic Income (UBI) – and even this was looked upon suspiciously by left-wing commentators as little more than a power grab from the right in order to dismantle welfare states and absolve themselves of responsibility for social care. It was a great conference for many different reasons, but it was clear that the topic of automation just wasn’t going to be taken seriously…at least not yet.

This experience contrasted with the next two occasions. The first was a discussion held under the Chatham House Rule geared towards exploring models of circular economy. It didn’t take long before automation was brought to the table – highlighted as something which will redefine labour markets, radically alter notions of productivity and consumption, and that unfortunately has the potential to exacerbate inequality even further if not directed towards a more citizen-focused devolved economy. The concept of UBI arose as a necessary consumption antidote to the shift, at least in transition, and measures of growth such as GDP were looked upon as already outdated and in need of a complete overhaul in order to accurately measure the flow of an economy within this new socioeconomic reality (or even within the current one).

This experience contrasted with the next two occasions. The first was a discussion held under the Chatham House Rule geared towards exploring models of circular economy. It didn’t take long before automation was brought to the table – highlighted as something which will redefine labour markets, radically alter notions of productivity and consumption, and that unfortunately has the potential to exacerbate inequality even further if not directed towards a more citizen-focused devolved economy. The concept of UBI arose as a necessary consumption antidote to the shift, at least in transition, and measures of growth such as GDP were looked upon as already outdated and in need of a complete overhaul in order to accurately measure the flow of an economy within this new socioeconomic reality (or even within the current one).

The final event was a discussion centred upon a talk by Charles Ross, Chair of the Brain Mind Forum. He takes the notion of automation very seriously and spoke about three key areas: robotics and employment, the ethics of artificial intelligence, and the long term impact of convergence between our technology, our bodies and our minds. It was his contention that much of the political discord we are seeing in developed economies at the moment (with specific mention of the rise of Donald Trump, and one could add the result of the recent UK referendum) is primarily the result of wage stagnation/depression, which is itself being caused by the ICT revolution and the inevitable move towards an automated economy.

This technological paradigm shift has the capacity to generate vast amounts of wealth and creative capacity, as is already self-evident, but at the same time begins to break down the relationship between labour and productivity that our modern socioeconomic context relies upon. This is causing a great deal of disaffection, which in turn is being projected onto wrongly perceived external threats such as immigration. The discussion this time took the rise of automation almost entirely as a given, perhaps unsurprising being a group who all had connections to IT, although there was disagreement on whether or not the end result would take a utopian form or be devastating to our collective psychology and a threat to the very foundations of the human condition.

As an emerging topic that is not yet fully recognised in some circles, there is a lot of work to be done to bring the imminent paradigm shift of automation into the public eye and the attention of policymakers. It’s also important to recognise that such radical change could occur on a timeframe even quicker than the devastating impact of climate change. In many respects it is because of the enormity of the climate change challenge that the potential problems of automation are not being addressed, and those currently paying the most attention are doing so primarily because of workflow gains, profitability and improved efficiency in business models.

There is so much to add to this topic that I will be revisiting it over the coming months. For now there are two things that I would add to the discussions I have been part of recently. My intention here is to contribute to the conversation and help bring it to the attention of those looking into areas of new economics and policymakers who are interested in strengthening economic resilience.

The first is that we need to define more clearly the difference between mechanisation and automation. A large part of the dismissal of this subject is the idea that “we’ve been hearing this for decades, and it never happened”. Many people just don’t believe this time will be any different, but that is because they are misinterpreting the issue being discussed.

The first is that we need to define more clearly the difference between mechanisation and automation. A large part of the dismissal of this subject is the idea that “we’ve been hearing this for decades, and it never happened”. Many people just don’t believe this time will be any different, but that is because they are misinterpreting the issue being discussed.

Even leaving aside the fact that General Motors at its peak had 850,000+ global employees and Facebook has about 15,000 for a far larger market capitalisation – i.e. the hyper-efficiency of the digital economy as it already stands – what people are missing when they refer to the automation revolution as mechanisation is one of its core components: artificial intelligence.

It is incorrect to think that the process of automation consists merely of factory workers being replaced by robotics that run through pre-programmed and repetitive tasks. This isn’t just an Industrial Revolution 2.0, and we need to make this clear to those dismissing its impact on such grounds. The changes that will result from this revolutionary transition are not just extensions of the mechanical capacity of human beings, but rather fundamentally change the notion of productivity through the power of increasingly omniscient system awareness and instantaneous plural decision-making. Machine learning and artificial intelligence goes well beyond an increase in production capacity and delivery speed, which were the hallmarks of the industrial revolution, as it has the potential to change the inherent nature of the workforce entirely. This is in addition to the overcoming of risk factors and workplace conditions that human beings should never be made to endure and could be a very positive outcome of the automation process.

The final point I would want to add (for now) is about how we might embrace some of the opportunities afforded by automation. Opportunities to redefine industries and social roles that are currently undervalued by a product-driven economic system – particularly those interactions that rely more on relationships over transactions. One of the points put forward very strongly at the PERC conference was how deeply undervalued the care industry, and caring for people in general, is to our current economic status quo. Most care activity occurs unpaid and increasingly unsupported, with terrible working conditions, yet it is one of the true cornerstones of a healthy and flourishing society.

By radically changing the landscape of labour participation in many previously booming sectors, perhaps we might be able to elevate areas that are economically marginalised. The role of creative industries and service-driven relationships that require deep human-to-human emotional interaction have the potential to be uplifted to new levels of status and recognition – not to mention pay and employment conditions – once the more mechanical aspects of our workforce become more fully automated.

The transition to a radically different system has already begun. It is now our collective responsibility to openly discuss what this means. Not just for the business models that might be able to take immediate advantage of it, but for the changes it foreshadows to the socioeconomic realities that we all feed into and rely upon. This is fundamentally different to the industrial revolution, because it gets closer to the core of the human condition. It requires us to formulate new ways of seeing ourselves as productive members of society, of connecting with others in a multiplicity of communities both fixed and transitory. Formulating together new narratives for what it means to positively contribute to the inter-generational project of humanity.

We have an opportunity to elevate global society away from the difficulties of subsistence living, empowering ourselves to seek out new landscapes of meaning and collaborative vision. Yet there is also the risk of doing a great deal of damage to our collective psyche, of enabling this next phase of human evolution to enslave rather than liberate us. Automation is a systemic revolution that runs throughout the structures that we currently build society upon – our production, consumption, education, politics, health and identity. We need to work diligently to bring this vital topic into the public discourse, and find ways to make the challenges it presents immediately relevant to policymakers, innovators and citizens alike.

Automation is happening. It’s important now to ask just what, and for whom, it is happening for.