What better way to get back into writing a futurist blog than to talk about cute robots, eh? Last weekend, I had the opportunity to go and check out the Robotville exhibition that was taking place at the Science Museum here in London. The exhibition was billed as ‘the most cutting edge in European robot design and innovation’ and although I seriously doubt that claim was terribly genuine, it was definitely something that any futurist would want to have a look at.

Unfortunately the exhibition was far too crowded, so it was difficult to get much time with any of the robots or their creators (it’s kind of hard to push your way passed wide-eyed kids enjoying an educational day out with their parents…). However, one thing that was immediately apparent is that the more human-like or ‘cute’ the robot was, the bigger the crowd around it.

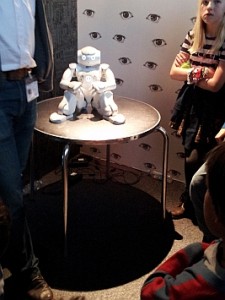

Whether it be intricate replications of human hands, all the way through to the Astroboy-like iCub (pictured here as it tracks and accepts a red ball – even showing signs of frustration in its eyebrows and mouth when teased with a constantly moving target), we are drawn to examples of robots that mimic our own attributes. One of the robots was even specifically designed to work with this response, its’ cherubic face and ability to make eye-contact designed to test our perception of the robotic cute-creepy continuum. I thought the eye-contact was a positive but felt that the baby face was a bit odd and disconcerting as it often held a blank stare. There was also an example of a robot designed to help autistic children read social cues, probably the most appropriate example of a genuine need for child-like attributes.

Whether it be intricate replications of human hands, all the way through to the Astroboy-like iCub (pictured here as it tracks and accepts a red ball – even showing signs of frustration in its eyebrows and mouth when teased with a constantly moving target), we are drawn to examples of robots that mimic our own attributes. One of the robots was even specifically designed to work with this response, its’ cherubic face and ability to make eye-contact designed to test our perception of the robotic cute-creepy continuum. I thought the eye-contact was a positive but felt that the baby face was a bit odd and disconcerting as it often held a blank stare. There was also an example of a robot designed to help autistic children read social cues, probably the most appropriate example of a genuine need for child-like attributes.

So there’s something here about our fascination with cute robots, and more generally with android-style automatons. Whenever I see my friends sharing a video about robots via social media, it’s invariably of the latest anthropomorphic creation and almost exclusively ‘cute’ in some way.

It’s understandable, we are hardwired to be interested in such forms. But it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on where the line between machine and robot is for you, and whether that line is dependent upon human attributes (or more widely, the attributes of animate life-forms in general).

I’m taking a guess that most people use the term ‘robots’ to indicate a certain capacity for human attributes rather than recognising the robots that help us in the manufacturing process, which we would often label ‘machines’. Semantic though it is, that our definition of what constitutes a robot as opposed to a machine is influenced mainly by whether or not they have some resemblance of a face intrigues me. Like many things, we have been heavily influenced by television and cinema in our understanding of robots; so it’s probably not surprising that our imagination tends to be relatively limited.

For example, Wall-E had to be given expressive capacity in the movement of his eyes before we found him adorable – and my use of a gendered possessive adjective to describe Wall-E gives away the game even further! I can’t bring myself to call Wall-E an it…because that somehow diminishes from the expressive, and sentient, existence that Wall-E encapsulates. Upon ordering a Roomba-style robot floor cleaner recently (review will be forthcoming), one of the first thoughts is to stick eyes on it to heighten its cuteness. I am actually more enamoured by the fact that it will have the capacity to map out the room, to respond to obstacles and self-regulate its need for energy, to mimic sentience even if only through an algorithmic simulacrum. But without the eyes, it just won’t quite reach peak awwwness.

So is it possible to create a new aesthetic not just for programmed robots but even for new forms of sentience? One that can be filled with identity and creative expression (I hesitate to use the word ‘personality’ here for obvious reasons) that we could relate to in a way that does not constantly assess the level of similarity to ourselves. As we strive to make robots more like us, is an opportunity being missed to widen our emotion of empathy away from its genetic imperative? Of course, we find it difficult to imagine possibilities because our experience of sentience is relatively limited. But that doesn’t mean the potential isn’t there to create new links and expand our concepts and cognitive domains.

My thinking along these lines is too new and raw to be of much use at this stage, so I would welcome thoughts from anybody reading this and please do comment below – even better, if you can point to some examples of robotic research and engineering being done in these kind of areas. It strikes me that an aspect of this will be in truly decentralised communication and co-ordination possibilities, something which immediately brings the capacity of robotics beyond the confines of how we usually experience life in our daily existence. Another possibility lies in modular technology, that allows form to be dynamic and sentience to adapt itself to different environmental and locational paradigms that fixed physicality cannot.

Ultimately, however, the change might have to come from our own perception of the robots and machines we create and how we relate to them. It’s not easy (to say the least!) to bypass deeply embedded evolutionary traits that instinctively equate sentience and individuality with aspects such as a recognisable ‘face’, responsive body language, recognisable vocal patterns or concepts of rationality based upon the human condition.

Ultimately, however, the change might have to come from our own perception of the robots and machines we create and how we relate to them. It’s not easy (to say the least!) to bypass deeply embedded evolutionary traits that instinctively equate sentience and individuality with aspects such as a recognisable ‘face’, responsive body language, recognisable vocal patterns or concepts of rationality based upon the human condition.

As we begin to more and more closely assimilate artificial intelligence with highly advanced engineering we should not see ourselves as limited by the biological necessities that have previously created a boundary for physical existence and the expression of identity. Although I can, of course, recognise the technical challenge and milestone that such efforts represent; we should always be striving to widen our horizons and embrace ever more progressive creative potential.

It’s often been said that in the future we will be able to embed intelligence into all of our technology. Forms of sentience will multiply exponentially, and will eventually even be able to autonomously create new forms of life that are even further removed from their biological ancestry. The field of robotics represents movement into identity formed by the basic foundational physics of the universe coming into collision with the heights of creative expression that humanity embodies, eventually bypassing the traditionally understood mechanisms of biology and requiring entirely new social and evolutionary paradigms.

We can no longer simply presume that our understanding of being, based on biological cognitive architecture, is equipped to deal with these newly changing boundaries of sentience never before encountered. In the relatively near future, we will need to widen our capacity to recognise individuality, rationality and sentient existence whilst finding new ways to enter into relationships with entities that we may have been the progenitors of; but that will eventually be our peers.