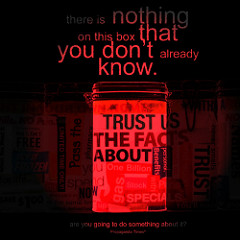

Image above by Mia Felicita Bertelli, CC

Seeing 2016 come to an end with a massive escalation of tension between the United States and Russia seems fittingly terrifying for a year filled with surreal geopolitical movements. Indeed, on a more mundane level, television writers are now facing the challenge of their work appearing bland and unimaginative when compared to the real world. We’re now well and truly through the looking glass and there doesn’t seem to be any sign of calming the waters of an increasingly turbulent world.

At the core of a lot of unease at the moment is what many people are referring to as a ‘post-truth’ world. Election cycles, policymaking and the media-driven narratives that accompany them have proven to be increasingly detached from evidence-based thinking and respect for a sense of truth in political discourse. There is apparently no longer considered much need to reference to facts in how we form our so-called democratic decisions. It’s not even required to be consistent in the lies told or opinions held from one day to the next, as the rise and rise of President-elect Donald Trump highlighted in clear terms.

It’s arguable whether or not this is a new phenomena. Maybe it’s just that universal online scrutiny and 24/7 communication have allowed us to unmask what has always been at the core of political rhetoric. The difference, though, is the extent to which “these lies are perplexing in their nakedness” as one commentator on This American Life recently stated. We have entered a period where mistrust of one another is so rife that calling someone out for lying can often end up only strengthening the support they receive. Beyond this, the erosion of trust has now reached a point where few sources of authority exist that can take us out of the tribalist race to the bottom.

All of this gets wrapped up in the ‘post-truth’ label, but is this new buzzword to describe our dissonance glossing over the deeper issue of conscious manipulation and propaganda?

Alongside this construction of transparent narratives (on all points of the political spectrum) there is the apparently new spectre of so-called ‘fake news’. The spreading of misinformation, knowingly or not, that has allowed a monstrous form of the grapevine rumour mill to take hold without much fear of repercussion for those seeding it. Although we should question why this has suddenly become a problem deemed worthy of coverage, it is clear that the digital platforms we rely upon are easily manipulated and prone to sensationalism based on falsehoods. Yet that doesn’t mean that the solutions offered are any less troublesome. It’s also a bit rich to see mainstream outlets pushing accusations of fake news whilst serving up a block of sensationalist clickbait headlines on every page of their own websites, in the form of those toxic advertising services that have become so popular over the last few years.

As a response to the fake news ‘epidemic’, we see governments, tech companies and news agencies rallying around solutions based almost exclusively on the censorship of information. Fake news is a real issue, but calls for the censorship of it are deeply suspicious as the line between fact and fiction is often not easy to clearly identify. We have already seen examples of companies such as Facebook accommodating repressive regimes such as the Chinese government.

Do we want to rely on unseen gatekeepers to decide for us what is true or false? Where is the burden of proof and on whose terms should information be dismissed as lies? Perhaps education and a cultural shift towards demanding evidence-based reporting should be the answer, rather than some twisted form of censorship sold to us for our own good.

Related to all of this, but unsurprisingly not a part of mainstream debate, are the realities of digital propaganda – the spreading of lies and fake opinion through astroturfing, media surrogates and planted stories. If we are going to censor fake news, shouldn’t we also include these and other forms of disinformation? Again, the question of who gets to draw the line becomes the pivot point of control that highlights who holds the keys to political decision-making.

Related to all of this, but unsurprisingly not a part of mainstream debate, are the realities of digital propaganda – the spreading of lies and fake opinion through astroturfing, media surrogates and planted stories. If we are going to censor fake news, shouldn’t we also include these and other forms of disinformation? Again, the question of who gets to draw the line becomes the pivot point of control that highlights who holds the keys to political decision-making.

Whilst the debate rages around fake news we should also be pushing for a higher degree of scrutiny on propaganda and the forms it will take in the future. For example, just this week The Guardian – often considered one of the few mainstream media outlets still committed to real journalism – has come under heavy scrutiny for its blatant manipulation regarding reporting on WikiLeaks that aligns with propaganda-driven political narratives.

What this all comes down to is that our world is increasingly covered in a layer of information that we take at face value without properly questioning who is delivering it. When you combine this with the move towards a kind of universal individualisation – where every person sees their own, customised version of the information layer – then propaganda can be delivered and curated at an individual level. Not just mass mainstream media or cultural hegemony; but an assault on the reality that personally surrounds you.

The more we develop the ability to cater digital information to the individual based on data profiling, the more we have created tools and opportunities to ideologically manipulate people at a fundamental level. Not only this, but we have handed control over this information primarily to private companies and government agencies that, from the outset, have an inherent conflict of interest when it comes to how they are used. Consider here the particularly chilling example of Facebook putting considerable effort into psychologically manipulating their users into experiencing negative emotions. But it’s all just for science, right?

It’s true that grassroot uses of these new communication tools can emerge quickly and effectively but, even though this can provide a counter-weight to these kind of power imbalances, it also means that extreme ideologies can develop a highly persuasive platform for dissemination. Again, this is occurring at the individual level and can be tailor-made often by our own ability to fool ourselves through confirmation bias and the echo chambers we can find ourselves in online. Our engagement is primarily happening through the screens that surround us, usually held in hand. We have developed a deeply emotional connection with our technology that brings these thoughts, ideas and perspectives directly into the core of our being.

The post-truth era we find ourselves in – and the accompanying accusations of fake news and its influence – is essentially a result of the increasing tendency to manipulate media narratives for political and economic gain. This manipulation coincided with (and was directly part of) a massive disconnection between citizens and structures of decision-making, along with an almost complete breakdown of trust between individuals and the social institutions that we rely upon. Government, media, finance, health, education, law, business … the disconnect is near universal with few clear options of a sensible path forward.

Our inability to make sense of a world captured by vested interests, extreme ideology and disinformation has formed a perfect storm of collective cognitive dissonance that is leading to severe levels of alienation, anxiety and civil unrest.

So what can we do to help overcome this? One of the most basic approaches is to start reconnecting with people – out in the world. Join interest groups, participate in debates and discussions, become part of your local community. Networks that have an open foundation of knowledge sharing and mutual respect will be more resilient to manipulation, particularly when these discussions are happening within the context of strong emotional bonds.

So what can we do to help overcome this? One of the most basic approaches is to start reconnecting with people – out in the world. Join interest groups, participate in debates and discussions, become part of your local community. Networks that have an open foundation of knowledge sharing and mutual respect will be more resilient to manipulation, particularly when these discussions are happening within the context of strong emotional bonds.

Secondary to this, but perhaps ultimately more important, is the development of new forms of education on critical thinking devoted to the digital sphere. The ability to discern the worth of different information is a vital skill that we have subsumed to a misguided sense of who holds authority over truth. The ability to ask the right questions (of the right people and organisations) and know how to get your voice heard in a way that promotes dialogue and accountability is a difficult skill to attain, but it is one that we must see as central to the proper education of future generations. This is learnt through practice as much as it is in theory. Unfortunately, I don’t think we can rely on the so-called wisdom of crowds to get us out of this one; as anybody who followed the political shill wars on Reddit throughout the US-election has seen ample evidence of. We need to develop a more widespread use of critical thinking to discern the value of information put before us.

Whilst doing this, we need to reach outside of our own echo chambers and disconnect from the digital filter bubbles that we have all found ourselves in. The level of influence that algorithms controlled by corporations with agendas and conflicts of interest can have on the way we find and use information online has been widely discussed, but in many ways this is also a phenomena that we inflict upon ourselves. Take a moment to reach outside of the usual corners of the internet that you frequent, to read research or reports from different perspectives, or entertain a contrarian view on your own beliefs instead of just those of others. We forget how quickly we can normalise a sense of righteous indignation without tracing back to the source of our opinions and seeing what kind of foundations they are built upon. At the very least, taking the time to get to grips with the thinking of those who you see yourself in opposition to will help you put forward a case for your own vision of the way things should be.

This brings us to the final point, one that I’ve made before on this blog, which is that we all need to take some responsibility in contributing to the shared narratives being created. We have the tools to circumvent false narratives, particularly when used collectively to record situations around the world and share them with one another. This doesn’t just have to be done through the written word, but can take any form of communication. One of the newfound capabilities highlighted by the Occupy movement, to pick one example, was the capacity to share footage of peaceful protesters being attacked by heavy-handed police. This ability to provide an unmediated view galvanised people around the world to take part in the movement. It is also why we saw the FAA ban the use of drones at the Standing Rock pipeline protests. The release of such footage undermines the political narrative whilst at the same time giving a stark view of the extent to which domestic police operations have become militarised.

The future of propaganda is one that will be increasingly pointed at us directly as individuals. It will shape the world around us to an ever greater degree as we continue to add utility to the personally-tailored digital overlay that we have placed over the world. Our response to falsehood and disinformation has to be the development of new ways to spread clarity and truth. Many of these tools are already at our disposal and we just need to use them more widely, others will be developed and shared by people committed to distributing power amongst us all.

The future of propaganda is one that will be increasingly pointed at us directly as individuals. It will shape the world around us to an ever greater degree as we continue to add utility to the personally-tailored digital overlay that we have placed over the world. Our response to falsehood and disinformation has to be the development of new ways to spread clarity and truth. Many of these tools are already at our disposal and we just need to use them more widely, others will be developed and shared by people committed to distributing power amongst us all.

Walking the path of truth requires us to all be more critical of our own views and beliefs; to be more open to the opinions held by others; and to understand that most of what we feel is correct belongs more to ideology than it does to fact. Truth emerges from practice more readily than it does from debate, from the results of our actions rather than the weight of our words.

We need to start talking less (or perhaps more directly into public discourse) and practicing more if we want to find a way to navigate ourselves out of this post-truth era. By doing so, we can start creating a shared future outside of the boundaries and dictates placed by those who yearn for control over and above the universal right to dignity and human flourishing.