So it’s Blog Action Day 2012, and as I’ve contributed to this great initiative in 2009 and 2010 I wanted to pick up the habit again and join in this year’s topic: The Power of We. Appropriately enough, I missed out on writing last year because of the breaking excitement of the Occupy movement which spread out from its American counterpart with hundreds of actions around the world on 15th October 2011. Thus we hit the one year anniversary, and the topic seems self-evident.

So it’s Blog Action Day 2012, and as I’ve contributed to this great initiative in 2009 and 2010 I wanted to pick up the habit again and join in this year’s topic: The Power of We. Appropriately enough, I missed out on writing last year because of the breaking excitement of the Occupy movement which spread out from its American counterpart with hundreds of actions around the world on 15th October 2011. Thus we hit the one year anniversary, and the topic seems self-evident.

But this post isn’t going to be another idealistic piece of rhetoric designed to pull the heartstrings and embolden your sense of activist courage. I’ve put a question mark behind the topic because I wanted to discuss an often overlooked (or should we say under examined) aspect of our reliance on collectivism as not only a method but a symbol of social progress. If the last year observing Occupy has taught me anything, it’s that concepts such as ‘we’ are never fixed and a whole host of problems emerge upon trying to define it and work within a conceptual boundary of all-inclusiveness.

In more ways than one, many people who fight for collective ideals are still immersed by their own personal narrative – the Story of I rather than the Story of Us. They’re not as complacent, and often more self-aware, but it’s still there. We (as in, all of us) are enamoured by our own journey, and particularly when it has aspirations to social utopianism and ‘making the world a better place’. But what is often overlooked is that we project imagined identities onto those we interact with. You do not interact with ‘me’, you interact with your image of ‘me’ – and the same occurs whenever groups of people band together under a moniker such as the ‘99%’. Problems arise when an affinity group begins to feel that it has a particular purchase on utopia – a vision that supercedes all other group’s criteria for positive social change. It is here where We becomes more about those who are closest to I than bringing Us together.

Behind the media narrative Occupy has been a story of numerous schisms and internal conflict between different affinity groups. From the outside perspective it represents the Power of We – indeed that is its core and most powerful message – but so far there has been little open reflection on the equally illuminating fact that most localities descended into various degrees of infighting and an inability to reach consensus on important issues. It’s understandable to want to avoid such discussion in the public sphere, but this need to sweep certain drawbacks of the movement under the carpet has only led to greater dissonance and conflict further down the line.

Behind the media narrative Occupy has been a story of numerous schisms and internal conflict between different affinity groups. From the outside perspective it represents the Power of We – indeed that is its core and most powerful message – but so far there has been little open reflection on the equally illuminating fact that most localities descended into various degrees of infighting and an inability to reach consensus on important issues. It’s understandable to want to avoid such discussion in the public sphere, but this need to sweep certain drawbacks of the movement under the carpet has only led to greater dissonance and conflict further down the line.

In many areas this notion of consensus-based decision making has even been abandoned for an approach that discusses ‘autonomy’ more than it does ‘consensus’. The approach has evolved from seeking a broad-based, collective We to one that looks more to the capacity for small affinity groups to band together towards particular agendas and actions. Again we see that We starts to be more about those closest to I than bringing Us together.

This form of autonomous organisation can work wonders – and a counter-argument would be that it often leads to effective social action where consensus-driven decision making stagnates and flounders – but it’s also indicative of the many reasons why the lofty aspirations of a year ago have been replaced by a sense of burnout and growing public apathy towards the movement. However you feel about Occupy (and it’s hard to be against the movement’s core aims), the fact remains that within the space of a year participation in the movement has dropped in most areas by up to 90% (based on observation and anecdotal evidence). One of the reasons for this lies with people who self-identify as Occupy but are unable to navigate the difficult terrain that exists when calling for We but relying more on a conception of I.

I have discussed some of these tensions in the past, and as far as I can tell they are to be found regardless of geographical location. Which means they speak more to our inherent inability to truly discover the universal, collective We then they do particular faults in particular places. It’s difficult to overcome our predisposition to be exclusive rather than inclusive, to be suspicious rather than welcoming, to be selfish over loyal. So who it’s always worth asking who is this We being constantly referred to, and can it ever be all-inclusive?

The internet revolution (for a revolution it truly is) has brought with it the capacity to communicate in collectives, to broaden our sense of participation in the global information matrix. The Power of We can be felt now more than ever, it seems easily within reach; for many of us just a few keystrokes or mouse clicks away (I have vague memories of some warlord called Kony…). Initiatives such as Wikipedia highlight the power of crowd-sourcing information (although with a distinct gender bias), whilst Kickstarter enables us to bypass the traditional crucibles of consumer power and go straight to the creators (how do you refund a crowd-sourced project?).

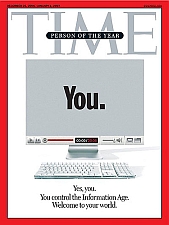

In 2006, Time magazine recognised this revolution in communication by giving their coveted Person of the Year award to You (yes, You). We all received the award, but we received it as individuals – as separate ego-driven identities with our own goals and aspirations, visions and agendas. The award didn’t go out to Us, it went out to You. There is something very telling here, even though the award was intended to highlight the Power of We it also points towards our capacity to become self-obsessed with crafting a digital identity in our own little slice of cyberspace (this blog, point in case).

In 2006, Time magazine recognised this revolution in communication by giving their coveted Person of the Year award to You (yes, You). We all received the award, but we received it as individuals – as separate ego-driven identities with our own goals and aspirations, visions and agendas. The award didn’t go out to Us, it went out to You. There is something very telling here, even though the award was intended to highlight the Power of We it also points towards our capacity to become self-obsessed with crafting a digital identity in our own little slice of cyberspace (this blog, point in case).

It points to the fact that we all experience life through one set of eyes, through one perspective on life, and that this will necessarily lead us to self-identify infinitely more easily than to discover our empathic duty to the rest of humanity. Can You ever really connect with Me over this medium? (The answer is yes…but).

Of course, I do not want for a moment to casually dismiss the massive capacity for social change that collective thinking can bring about. When it comes to our ecosystem and the need for environmental sustainability the Power of We is really one of the only narratives that will overcome impending calamity. When it comes to dictatorial regimes or laws, the Power of We allows those who are oppressed to band together and overthrow their oppressors. When it comes to systemic issues such as those found in the global financial system it is the Power of We that forces action and keeps those who make promises to account. When it comes to charitable causes, the Power of We takes mere days to raise millions of dollars and have real impact on the lives of countless thousands.

But for every positive story behind the Power of We there is a negative one. And I’m not just talking about the violent and despicable examples of group identity (I refuse to adhere to Godwin’s Law in this post…so I’ll bring up Jonestown instead). I’m more concerned, as the few of you who are loyal readers might know, with those nuanced areas of the human condition where we do not live up to our lofty ideals and imagined identities. The ideal is inspiring, but in order to truly discover the Power of We it is important to overcome simplistic notions of identity and arrive at a more honest and authentic formulation of what it means to relate to other human beings in a collective environment.

The true Power of We will be born in a form of discourse that encourages us to focus more on our own flaws then on the flaws of those our affinity group might see themselves in opposition with. By transforming our reliance on defending the ego and its ideological territory into a dialogue that promotes dynamic, transparent interaction with individual viewpoints this elusive Power of We might just be discovered. Otherwise, it risks being co-opted as people are prone to being dazzled by spectacle and the alluring empowerment of group identity; creating a We that moves more out of primal impulse and groupthink than any genuinely shared reality.

There is no We without I, and that dichotomy must be put at the forefront of our minds when discussing our supposed capacity to collectively create and steer our social and political realities. What’s important is to find a way to bring this relationship between We and I into constant communication with a new level of truth and honesty that draws us into the compassion, charity, belonging and diversity that is to be found when we discover a way to reach beyond one another’s masks whilst also removing our own. Which is why I’m less enamoured by the Power of We and more so in discovering the Power of Us.

There is no We without I, and that dichotomy must be put at the forefront of our minds when discussing our supposed capacity to collectively create and steer our social and political realities. What’s important is to find a way to bring this relationship between We and I into constant communication with a new level of truth and honesty that draws us into the compassion, charity, belonging and diversity that is to be found when we discover a way to reach beyond one another’s masks whilst also removing our own. Which is why I’m less enamoured by the Power of We and more so in discovering the Power of Us.