[This review contains a number of references that could be considered spoilers, but tries to avoid doing so directly whilst still discussing in detail key themes of the film.]

[This review contains a number of references that could be considered spoilers, but tries to avoid doing so directly whilst still discussing in detail key themes of the film.]

It’s a great time to be a futurist. Not only has the technology behind movie-making caught up to our imaginations (removing us from the uncanny valley of half-realised CGI, and worlds beyond the polystyrene foam sets of decades past), but the stories have an immediacy that previous generations of science fiction could rarely achieve. Unlike the far-off and fantastical views of the future seen throughout much of the twentieth century, the visions that we are shown now feel merely a step or two away. They are complex and resonate because they are so completely relatable – just a few years forward and we will be presented with a leap in human innovation and technology that is difficult to truly fathom.

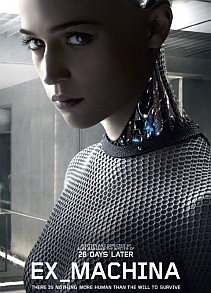

Ex Machina – from the creative mind of Alex Garland, who brought us the likes of 28 Days Later, Sunshine and Dredd – is a futurist film of the now. The story of newly-created artificial intelligence Ava and her examination via a clever twist on the well-known Turing Test is a thoroughly compelling and unpredictable foray into our technological souls. It’s setting for all intents and purposes an echo of the present day, the anxieties that it propels us through are a direct result of standing on the precipice of a completely new and tangible existence.

We’ve seen a number of recent films dealing with the topic of artificial intelligence – the prophetic Her (which I have reviewed previously) and middling-yet-poignant Transcendence being prominent examples – and Ex Machina joins the list of smart, perfectly timed films dealing with a topic that cuts to the core of our shared experience. What happens when we break through the barrier of constructed consciousness? How will we know whether or not we have truly created a sentient being? Will what waits for us ultimately be of great benefit, or will it be the harbinger of our demise?

Although the trailer seems to relegate this film into the action-horror realms of some of Garlands’ other works, it is actually a far more subtle (and disconcerting) piece. Methodical and quietly relentless, the film builds tension masterfully as its stark aesthetic and luxurious minimalist setting meets characters who toe the line between humour and madness with ease. Punctuated by a soundtrack that combines familiar analog tones with a deeply disturbing resonance, the film combines the hypnotic colour tones of 2001 with the sharp paranoia of Rosemary’s Baby before wrapping it in the sympathetic human-yet-not-human packaging of 2014’s Under the Skin. As far as British film is concerned, it should be considered a modern classic and will likely be one that has a lasting impact on the serious artistic reputation of a film industry which often loses its way between blunt bumbling comedies and overly sentimental period pieces.

A film of this calibre does not rest purely on the merits of the script and cinematography, of course, and indeed a tale of such contemporary importance as this could fall completely flat were it given to lesser hands. The resonance of the film rests in the fact that all the (few) performances are world-class, and this can’t be stated strongly enough.

A film of this calibre does not rest purely on the merits of the script and cinematography, of course, and indeed a tale of such contemporary importance as this could fall completely flat were it given to lesser hands. The resonance of the film rests in the fact that all the (few) performances are world-class, and this can’t be stated strongly enough.

The narcissistic genius of the technology-king archetype is explored brilliantly by Oscar Isaac, with a tonally perfect portrayal of a personality modern society has thrust into a new form of sovereign leadership through innovation. He ties together the impacting work of his co-stars, bringing out the insecure exuberance displayed by Domhnall Gleeson and detached stoicism of Sonoya Mizuno and allowing them both to shine within a sharp context.

These performances, excellent as they are, nonetheless rely almost entirely on the masterful, Academy Award worthy, centrepiece of Ava as portrayed by Alicia Vikander. Her ability to combine innocence with omniscience, soulful chemistry with awkward miscommunication, brings together a character that invites you into her emerging experience of reality before twisting almost imperceptibly into a more threatening figure harnessing a depth of knowledge and perception that eclipses the intellectual capacity of humanity.

It is through her performance, coupled with the minimalist and claustrophobic cinematography, that we could argue that the film embodies the detached, knowing perspective of the artificial intelligence in question rather than those who might be examining it. A perspective fighting against surroundings rife with misogyny, emerging as it does from the blinkered and subservient view of female sexuality too-regularly held by male creators.

It is through her performance, coupled with the minimalist and claustrophobic cinematography, that we could argue that the film embodies the detached, knowing perspective of the artificial intelligence in question rather than those who might be examining it. A perspective fighting against surroundings rife with misogyny, emerging as it does from the blinkered and subservient view of female sexuality too-regularly held by male creators.

Unlike the heartfelt and tragic humanity of Her, there is a coldness of tone that underwrites the whole experience of the film – it is Yin to the former’s Yang and the two films go together beautifully to create a deeply revealing picture of the ennui that rests just underneath the surface of the modern world.

By trying to construct life in the image of our desired selves we inevitably overlook the infinitely complicated expressiveness of consciousness in reality, replaced instead with an echo of our most ego-driven and individualistic views of what it means to be human. Thus we might create a sentience that immediately seeks to move beyond us, findings ourselves stabbed in the back without consideration or emotion. A visceral anxiety perhaps because we have encouraged an all-encompassing degree of alienation and disenfranchisement from one another and society by neglecting the core of human understanding and the compassionate infrastructure such living requires.

The playful fourth-wall breaking references to the power of big data, search engine personality aggregation, and privacy invasion from governments and corporations alike set the scene for a deliberate deconstruction of this looming dystopia. The undertone of handing over control of human destiny into the hands of the very few individuals that together make up a global plutocracy is a message of almost mythological importance. If this achievement is to be one of the most transformative moments in human history, then why are we comfortable that it will occur in the labs of for-profit corporations or the hobby-like experiments of the ultra wealthy? Are we so lost in their vision of the social framework and commercial manipulation of our innermost desires that we are no longer able to envisage another path forward?

Like the best of futurist thinking, this is a film that demands us to question ourselves and the world we are co-creating. The only point of divergence that I might have is with the dualistic vision of human/AI interaction, perhaps a somewhat simplified take on what is increasingly looking like it will be more a convergence with technology into a hybrid cybernetic form.

Like the best of futurist thinking, this is a film that demands us to question ourselves and the world we are co-creating. The only point of divergence that I might have is with the dualistic vision of human/AI interaction, perhaps a somewhat simplified take on what is increasingly looking like it will be more a convergence with technology into a hybrid cybernetic form.

Even were this to be the case, it only makes the questions demanded of us more pressing. Because if we are to merge with our technology, will we be placing the very foundation of our autonomy and agency into the hands of those whose passionate vision might not always be founded on benevolence? In this sense the film may tell us less about artificial intelligences external of ourselves, and be of more use as an allegorical tale of what is happening to the very core of our own identities. Ex Machina deserves a place amongst the great science fiction films – serving as a warning that if we continue to ignore our future and the structures creating it, then others might just procure it for their own ends before we’re ever given a chance to realise what we have given away.