The British Library has proven itself time and again as curators of some of the most interesting and unique exhibitions in a city famous for its museums and galleries. Expectations were therefore set high for their most recent look at the history of propaganda – the methods it uses, the topics it focuses on and the ubiquity of its existence.

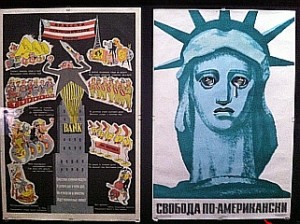

From the first use of the word in a 17th century Catholic text (Congregatio de Propaganda Fide) through to the instantaneous and ever-changing hivemind of the Twittersphere, with dips into the Olympics, nutritional PSAs and anti-semitism, it was made clear that propaganda is a tool used by every nation; directed at all kinds of people; for many varied purposes.

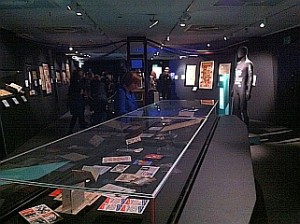

It has to be said from the outset that the design of the exhibition itself was fantastic. The space is relatively confined and so needs to be used creatively, something that the thematic groupings and angular partitions did very successfully. Greeted upon entry by a corridor of faceless, jet-black mannequins – each one displaying a poignant quote on its chest – an ominous tone was set from the outset.

It has to be said from the outset that the design of the exhibition itself was fantastic. The space is relatively confined and so needs to be used creatively, something that the thematic groupings and angular partitions did very successfully. Greeted upon entry by a corridor of faceless, jet-black mannequins – each one displaying a poignant quote on its chest – an ominous tone was set from the outset.

This helped establish a topic fundamentally about deceit and the dismissal of large swathes of humanity and human activity as undesirable and therefore worthy of contempt or destruction. The mixture of audiovisual displays with the expected collection of posters, books and pamphlets provided an engaging journey through the sights and sounds of this often sinister aspect of the human condition.

There was, however, an interesting dissonance to the exhibition. Whether it was because the curators had to rely primarily upon objects held in the British Library collection (although there were clearly a lot of items on loan from a number of institutions), it became evident that large aspects of the topic were under-represented. Depictions of civil liberties movements from slavery, through segregation, feminism to Occupy seemed like footnotes in an exhibition predominately (albeit understandably) centred on war and national identity.

As a friend who also attended noted: women seemed noticeably absent from the exhibition. By this she meant specifically that propaganda material not merely about or directed at but created by women (from the suffragettes to the Guerrilla Girls) was an avenue ripe for interpretation that didn’t find its footing amongst a very state-centric, nation-focused, male dominated idea of propaganda and how it manifests. If we also consider the example of Occupy, a single poster was used to discuss the subversion of propaganda motifs by anti-capitalist protestors – a missed opportunity when the Museum of London collected a large number of objects and ephemera from one of the most clear examples of (highly successful) grassroots propaganda in recent memory.

The exhibition also seemed to falter at the last hurdle, failing to capitalise on the sharp focus that could have been placed on the use of propaganda in the 21st century. We had the Twittersphere represented by a wall of live tweets and representations of hive mind activity (a truly impressive installation), coupled with a discussion on the Iraq war and its WMD justification that afforded a surreal meta-display from Alistair Campbell (Director of Communications and Strategy for Tony Blair at the time) who was spinning propaganda on past propaganda in an exhibition on propaganda in a video asking: who are the propagandists?

This served to highlight the role that media conglomerates play in disseminating propaganda from many different sources, but beyond a cursory exploration of the theme within the very specific context of Iraq there was a distinct lack of modern examples and contemplation on how we are affected by these techniques in our lives today. Indeed, we are left with the impression that the Iraq war was itself a conflict of the past – something to be referred to only with the newspaper headlines that instigated it over a decade ago – rather than an ongoing war with devastating results most acutely felt by innocent civilians. A sense of the immediate relevancy of propaganda was lost somewhere along the way.

Consider the role that Wikileaks and whistleblowers have played in subverting state authority; the cult of celebrity and the multi-billion dollar industry that supports it; dummy social media accounts that push agendas in supposed displays of ‘organic’, ‘grassroots’ opinion; the ‘War on Terror’. The implication of technological advancement, Big Data and how worldwide thought trends help enable rapid, dynamic forms of propaganda to be disseminated directly into the demographics that wish to be impacted. The ability for the general public to fool ourselves, engaging in examples of almost hysterical mob behaviour whereby our ability to build upon collective error with the help of social media and online discussion platforms has reached some eye-opening proportions. The private sector lobbying that sways opinion on pivotal topics such as climate change through publicly invisible means. The political slogans and campaigning that whips us into fervor – not a single Yes We Can! poster in an exhibition that began with a great discussion on the ancient practice of relating heads of state with depictions of divinity.

It must be to the credit of the exhibition, though, that these questions are raised. The timing of the exhibition was perfect, opening a month before massive revelations on the NSA brought us a new saga of government deceit, intrigue and propaganda on a global scale and closing during a week that will for the foreseeable future be remembered by shocking images of skyscrapers collapsing amongst human calamity.

It must be to the credit of the exhibition, though, that these questions are raised. The timing of the exhibition was perfect, opening a month before massive revelations on the NSA brought us a new saga of government deceit, intrigue and propaganda on a global scale and closing during a week that will for the foreseeable future be remembered by shocking images of skyscrapers collapsing amongst human calamity.

Hidden subtexts could be felt throughout the varied topics: the clash of civilisations; enemy of the state vs the state as enemy; propaganda as a biological basis of the human condition; social engineering; cynicism of the political elite; and the sheer ubiquity of the activity across every geographic location and all periods of time. All of this wrapped up in the sense that with social morale dropping rapidly, could it be that propaganda techniques meant to evoke and enrage have spectacularly and quite directly become the cause of our postmodern ennui?

We currently exist in an era where the ability to disseminate propaganda instantaneously, and direct it to very specific demographics, has crashed into our capacity for individuals to subvert this propaganda (be it state, corporate or ideology based) with equal flexibility. What we are left with is a confusing landscape of opinion and counter-opinion contextualised by a reactionary, impulsive, infinitely distractible culture which promotes short-termism whilst eroding our capacity for critical thinking. The postmodern condition is typified by this multiedged irreality, with the result being a desperate search for genuine experiences and authentic voices that plays neatly into the agenda of those who understand that the language of modern propaganda is one that must now be expressed invisibly wherever possible.

The propaganda we see clearly (Fox News, looking at you) becomes a blunt force weapon used against the lowest common denominator. The truly insidious manipulation occurs through methods that are unseen and often undetectable – leading to a pervasive mistrust of all sources amongst those actively seeking to form educated opinions, a mistrust that only serves to further fuel public apathy and malleability across all sectors.

In a context within which the psychology of propaganda and its impact is understood better than ever, combined with the technological capacity to create new forms of ideological manipulation, the fact that we’re left with a feeling that the content of this exhibition applies mostly to our sense of the past is something to be concerned about. This is not really the fault of the creators of the exhibition – they should be commended for an exemplary and thought-leading example of modern design, perfectly timed – but rather for the propensity that we all have to be steered by unrecognised influences and subtly encouraged prejudices.

This should be particularly poignant so soon after the anniversary of a terrorist attack that has become common vernacular (an act caused by propaganda, distilled by propaganda, and maintained by propaganda), that spawned a seemingly never-ending ‘War on Terror’ and media conflagration with state agendas leading to conflicts still ongoing a decade later against a backdrop of increasing levels of extremist ideology, regime change across the globe, and millions of innocent casualties.

This should be particularly poignant so soon after the anniversary of a terrorist attack that has become common vernacular (an act caused by propaganda, distilled by propaganda, and maintained by propaganda), that spawned a seemingly never-ending ‘War on Terror’ and media conflagration with state agendas leading to conflicts still ongoing a decade later against a backdrop of increasing levels of extremist ideology, regime change across the globe, and millions of innocent casualties.

Of the tens of thousands who have visited this exhibition over recent months, there will be many who were left with the same uneasy feeling – who knew that something was missing, that the examples of propaganda they see from all angles day-in and day-out had not been adequately represented. For an exhibition to stir such a deeply complex emotional reaction amongst its audience is an achievement in its own right, and it is within this hidden subtext whether intentional or not – the invisible propaganda that speaks from between the lines of the exhibition itself – that the real strength, and terrifying message, of the exhibition is truly to be found.

The run for this exhibition has recently finished, but for those interested in more you can purchase the comprehensive guide to the exhibition at a reasonable sum through the British Library website here.

![[Review] Propaganda: Power and Persuasion](https://www.futureconscience.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/propaganda2-125x125.jpg)